2020 4th Quarter Market Commentary

-The Good, The Bad and The Ugly-

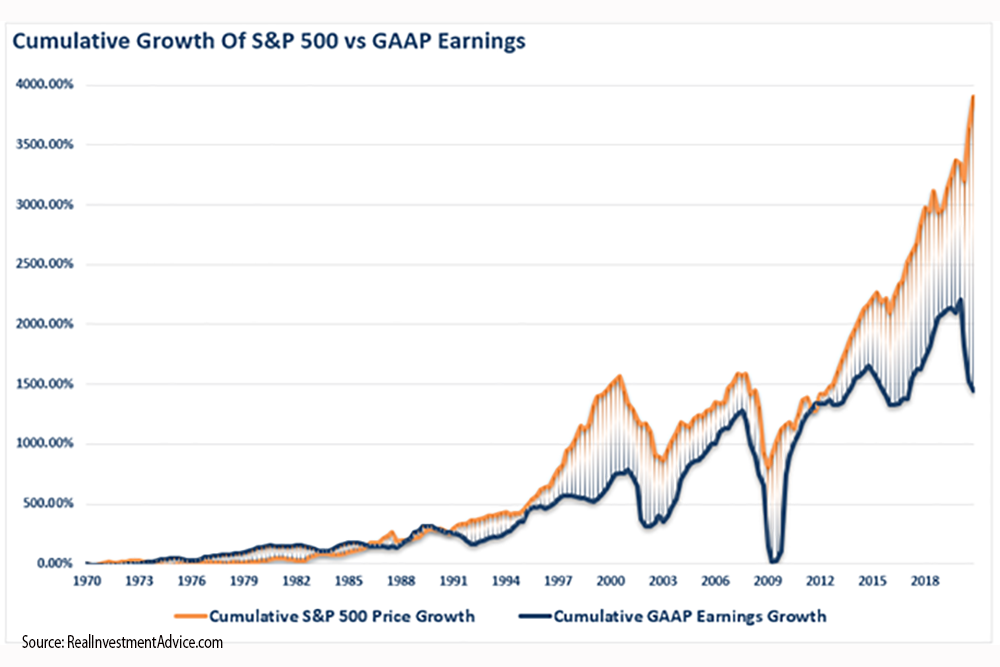

This graph highlights the stark dichotomy between what investors view as “good” and “bad” on the current investment landscape. The tan line traces the cumulative growth of the S&P 500 over the past half century. Most noteworthy is the explosive growth in the nearly dozen years since the end of the Financial Crisis. By contrast, the blue line shows how severely corporate profits were impacted by 2020’s pandemic-induced recession. Never in the half century covered here has the difference between stock prices and underlying profits been so profound.

While corporate profits may be the best indication of economic strength, investors focus on a great many factors in making their investment decisions. The following paragraphs present an inventory of positive and negative issues currently affecting the economy and securities markets. The negatives significantly outweigh the positives because, for more than a decade, the government has prevented natural cyclical corrections that would have eliminated excesses built up in traditional business and market cycles. Doubling down on that success, the government introduced unprecedented stimulus to lift the economy out of the painful early-2020 recession. At least in the short-term, stock and bond market strength provides powerful evidence that positive factors outweigh the more numerous negatives. The question remains open as to whether positives can continue to prevail over longer periods of time.

The Good

While a number of these factors may ultimately lead to negative results, they are currently on the positive side of the ledger, because they have led and continue to lead to at least near-term favorable market and/or economic results.

- Stock prices are at or near all-time highs in most of the world.

- Ned Davis Research indicates that its “Elite Eight” companies—Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google, Microsoft, Tesla and Nvidia — grew by 65.6% last year.

- Through the end of October (most recent data), on a 12-month basis, foreign buying of US stocks had never been higher.

- Active investment managers are displaying near record optimism. Broader investor sentiment is also extremely optimistic.

- Last year, Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren indicated that the Fed may end up buying stocks to ward off a recession.

- Strongly rising housing prices have boosted homeowners’ wealth.

- Government spending is at record levels.

- Already at record levels, more stimulus is coming in the US, both monetarily and fiscally. Many central banks around the world have also committed to continuing heavy stimulus.

- Fed actions of the past decade seem to confirm that the central bank has assumed a third mandate to keep stock and bond prices elevated, in addition to maintaining a stable currency and maximum employment.

- Massive stimulus has substantially raised the personal savings rate, which has the potential to increase future demand.

- US third quarter GDP increased at a 33.4% annualized rate.

- Despite the enormous second quarter decline in GDP, the market capitalization of US companies increased by more than $13 trillion from the end of the first quarter to year end.

- Securities analysts expect a very powerful earnings bounceback in 2021.

- Analysts are forecasting an increase in real 2021 GDP of about 4.5%.

- A great many jobs lost in the recession have been reinstated.

- Interest rates have begun to rise from extremely low levels, which should improve the health of the banking system.

- Vaccines are showing great promise in slowing the spread of the virus.

The Bad

- The pandemic continues to produce huge disease and death totals. The virus is still spreading aggressively, now with several variants. We can’t know yet what long-term effects might emerge.

- The pandemic led to a collapse of domestic and worldwide GDP. Despite the 33.4% Q3 annualized growth bounceback, analysts expect full year 2020 US real GDP to contract between 2.5% and 3.0%, producing one of the worst years in US economic history.

- Notwithstanding the expectation of strong stimulus, a double-dip recession remains a possibility in many parts of the world, even a probability in the Eurozone. Fed Chair Jay Powell recently stated that the outlook for the economy has become “extraordinarily uncertain…(and)… will depend, in large part, on the success of efforts to keep the virus in check.”

- After completing the initial powerful bounce from the depths of the recession, economic growth for the next few years is forecasted to be quite slow both in the US and internationally. Longer-term forecasts are for sub-2% growth for both the US and the Eurozone. The policy-setting panel of the International Monetary Fund warned: “The crisis threatens to leave long-lasting scars on the global economy.”

- According to Opportunity Insights, the number of open businesses in the US fell by nearly 30% last year. The National Federation of Independent Business stated that a quarter of small businesses say they will have to close their doors in the next six months if economic conditions don’t improve— up from 20% last month. A Goldman Sachs survey taken in November showed that only 60% of small businesses expect to survive. That expectation has gotten progressively more pessimistic. The resulting prospect for employment is dire.

- According to Bankrate.com, just 39% of Americans can afford a $1,000 unexpected expense. The recession has dramatically accentuated income and wealth inequality.

- Despite the relatively consistent employment recovery, a full recovery of private sector jobs that were lost in March and April is still a long way off.

- Unpaid residential and commercial rent may lead to an abundance of permanent defaults, significantly increasing tenant and landlord bankruptcies.

- Commodity prices have been climbing for several months, which could lead to broader inflation and higher interest rates. Higher rates could dent corporate profits and could pose an existential problem for overleveraged companies and governments.

- More than a decade of bailouts and other stimulus has piled unprecedented amounts of rescue debt on top of already excessive debt levels built up over many decades. While that debt creation helped to pump up spending in the short run, it has pulled future demand forward. Historically, high debt levels have led eventually to slower GDP and payroll growth.

- In their Third Quarter Review and Outlook, Hoisington Investment Management Company’s Van Hoisington and Lacy Hunt wrote: “The U.S. is caught in a debt trap,… (a) condition where too much debt weakens growth, which elicits a policy response that creates more debt that results in even more disappointing business conditions.”

- Excessive debt is widespread, and its quality is declining. The surge in sovereign debt downgrades in 2020 has surpassed those in all previous crises over the past four decades.

- S&P Global recently reported: “Higher leverage, together with a more challenging operating environment, has led us to downgrade 22% of corporate and sovereign issues globally.”

- Much of the rescue and stimulus money was intended to boost the fortunes of Main Street. The portion of that money which did not find its way into the economy found its way into the waiting arms of Wall Street, boosting stock and bond prices aggressively. That process has continued so long that investors have come to assume that it will be there as needed to prevent any meaningful decline in securities prices, accelerating extreme valuations and excessive bullishness.

- The S&P 500 price to earnings and price to sales ratios are currently at record levels. The Ned Davis Research universe of stocks is also at a record high P/E ratio and is three standard deviations above that universe’s 40-year median. An average of all major valuation measures is at all-time high levels of overvaluation.

- The Elite Eight stocks profiled in The Good section saw their average earnings increase by 12.4% in 2020 and sales by 12.1%, good numbers in any year. They only look deficient when compared to the stocks’ 65.6% increase in price. That advance elevated the stocks’ average P/E ratio to 46.4 and P/S to 8.1. Ned Davis commented: “I have never seen large cap stocks at these kind of valuations except perhaps near major peaks like 1968, 1972, 2000 or 2007.”

- Investor optimism is now at a level at which the market has historically struggled. The volume of IPOs and secondary offerings, representing selling by corporate insiders, is near record levels.

- Foreign investors have demonstrated great interest in US stocks and have built their US equity holdings, as a percentage of foreign-held US financial assets, to their highest level since 1969. More recently, the timing of such investors was extremely poor as they similarly recorded record levels of buying before the bear markets that began in 2000 and 2007.

The Ugly

Warren Buffett’s favorite valuation comparison is an especially valuable tool. Market capitalization compared to the size of the economy typically is an excellent approximation of the average of all major traditional valuation measures. The study goes back to the mid-1920s and currently shows the equity market to be more overvalued than at any other point in 95 years. Past equity markets have suffered hugely negative outcomes from every prior major valuation peak, even from less overvalued levels than today’s. From the next three highest peaks of overvaluation, the S&P 500 declined by 89%, 50% and 57%. In those three instances, it took 25 years, 16 years and 11 years respectively for the S&P 500 to again reach its prior peak. The vast majority of investors would be unwilling to wait that long.

When stock prices far exceed their normal relationship with underlying fundamentals, there is always the potential that the fundamentals could improve and rise to meet price. Over 95 years, however, that has never happened. Price has always declined from major overvaluation peaks to realign with underlying fundamentals. The odds strongly favor that happening in the present instance as well.

One of the most widely applauded features of recent government financial rescue programs has been the bailing out of companies otherwise financially sound but whose survival was endangered by the pandemic. Unfortunately, the programs have also rescued a large number of zombie companies. These are defined as companies not earning enough even in non-pandemic times to cover the interest on their outstanding loans. A recent study showed that at the end of the third quarter, 26.2% of Russell 3000 companies experienced three-year pre-tax earnings before interest expenses in negative territory. Eventually, companies with that profile may no longer be rescued, and investors who have not done proper research may suffer significant losses.

In recent years, algorithm-driven machines trading with other machines have dominated equity markets. Because the machines have learned most of their market history in the past few years, they may be susceptible to making major trading errors if prodded by a factor such as sharply rising interest rates — unseen in recent years. Programs that protectively sell into weakness could flood the market and decimate prices, as portfolio insurance did in 1987. There is potentially much bigger algo-driven volume today, and the exit doors are not nearly wide enough.

Perhaps most frightening is Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren’s speculation that the Fed may at some point turn to purchasing equities to try to avoid or lead the country out of recession. Besides further exacerbating the income and wealth divergence between rich and poor, such an action would destroy any remaining semblance of free investment markets in this country. The Fed has gone well down the road already in eliminating free domestic markets, but that’s a subject for another day.

The Dilemma

What do we do with all these good, bad, and ugly conditions? Of course, that answer may vary from investor to investor based on age, circumstance, and investment objectives. And individuals’ level of confidence or fear in large part varies based on recent investment experience. In this country, confidence is highest among those who were willing to accept the risks attendant to owning stocks like the Elite Eight, which led the S&P 500 to an 18.4% return in 2020, bouncing back powerfully from the 35% decline in the spring. Not so heavily affected by the handful of super-high-valuation market leaders, the New York Stock Exchange Index, which includes all stocks trading on that exchange, produced a far more modest 4.4%, having been in negative territory for a major part of the year. Eliminating the US from the equation, the World ex US index edged into the black near the end of the year with a meager 1.1% return.

After more than a half century of work in this industry, I confess to having a powerful bias toward outcomes that I have personally watched unfold without exception over the decades from substantially overvalued conditions. Since the consistent behavior of stock prices reverting to historically normal relationships to their fundamental means goes back even much farther than what I have experienced, I accord that expectation a very high level of probability. There still exists a crack for the unprecedented to sneak in. At the broad systemic level of this country’s stock market principles and practices, it has always been a loser’s wager to bet that “It’s different this time,” although that belief has been fervently held by every generation.

It is possible that the Federal Reserve and other governmental agencies have already gone so far as to be unable to pull the country back to historically normal levels of debt and to adopt a hands-off approach to the nation’s equity markets. Should that realization come to guide future action, there would be a possibility that the government would so pump up the money supply that stocks, real estate and most everyday goods and services might be raised to new normal levels. Such action, however, would have monumental effects on the world’s financial system and would cause massive dislocations. It, therefore, remains a low probability, though not zero. I hope to write more on this in time.

Potentially, we never go back to historic normalcy. The stock market’s eventual experience of reversion to the mean, however, is overwhelmingly the most likely outcome.

If reversion to the mean is most likely, it’s hard to understand why equity investors — traders excepted— are willing to spend more than twice what is normal relative to underlying equity fundamentals in light of expected lower than normal economic growth domestically and internationally for several years, after an initial strong, but brief, bounce back. Perhaps the dominant assumption is that investors should continue to ride the Fed and a new Democratic Congress without regard for underlying fundamentals. That assumption is historically problematic, but has been successfully practiced since the government seemingly took as a mandate eleven years ago to protect markets from all potentially significant declines.

Let me close with words of wisdom from a few of the world’s most successful investors over the past several decades. Having long ago abandoned portfolio management, Jeremy Grantham, co-founder of GMO, penned Waiting for the Last Dance earlier this month. In it, he described the current market as “… one of the great bubbles of financial history, right along with the South Seas bubble, 1929, and 2000…. for the majority of investors today, this could very well be the most important event of your investment lives.” He went on: “The one reality that you can never change is that a higher-priced asset will produce a lower return than a lower-priced asset…, and the price we pay for having this market go higher and higher is a lower 10-year return from the peak.”

Mohammed El Erian, former manager of the Harvard endowment and former co-CIO of PIMCO, recently identified the question he asks himself whenever he makes an investment decision: “Is this a mistake I can live with?” In a similar vein, Arthur Cashin, head of floor trading for UBS and one of the very best market historians, has often offered counsel that we should heed in virtually all aspects of our lives. He says that when he goes into a room, he always looks around to see where the exits are. That may be especially wise advice for all of us today, as we face highly uncertain health, economic, and market conditions.

By Thomas J. Feeney, Managing Director, Chief Investment Officer

Mission’s market and investment commentaries reflect the analysis, interpretation and economic views and opinions of our investment team. They are not intended to provide investment advice for any individual situation. Please contact us if we can provide insight and advice for your specific needs.